Labels are an often used but unfortunate barrier in the art world. Minimalism is one that has been regularly applied to concert music, dance, and opera, but it tends to put any work in a box. Lucinda Childs and John Adams, the principal collaborators for “Available Light”, fall into this category. But by the time Childs’ revival of her minimalist work concluded on Saturday evening at Disney Hall, the label seemed mostly irrelevant. What remained was a calming distillation of clarity and order, and a harmonious reflection in movement of John Adams’ symphony on tape, “Light Over Water”. Like many music/dance experiments of the same era, “Available Light” was a collaboration, but one that allowed Childs and Adams to work independently on a final result.

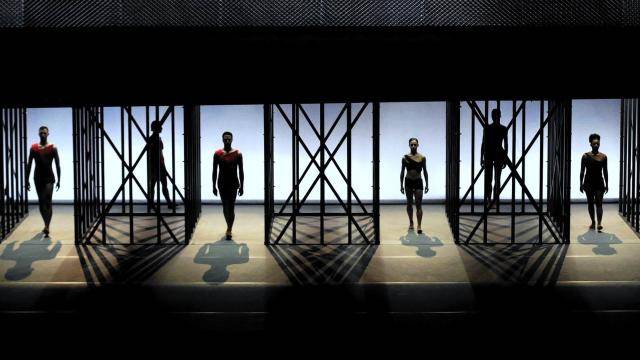

Originally made in 1983 for the Stages and Performances series at MOCA, it was one of several collaborative works that linked, dancers, composers, designers, and other artists in works presented throughout Los Angeles. The current version marks a return after decades, and comes packaged with new, stripped down costumes (Kasia Walicka Maimone’s designs make the dancers sleeker but less anonymous than the originals)) and a slick bi-level set by Frank Gehry who designed the set for the original performances. The dancing space is divided into two spacious, luminous off white stages, with the upper overhanging level supported by clusters of see through piers. A towering drop of chain link fencing hangs at the back the upper level. It all looks industrial, artsy, and expensive.

Like similarly charged particles, the dancers sort out some natural state of equilibrium while they move and when they come to rest.

“Available Light” is something of an understated odyssey. The slowly evolving movement keeps the dancers onstage for an hour of continuously evolving movement. The piece is built on repeated cells of motion danced in small unison ensembles Once used they are abandoned for new ones. The eleven dancers are divided into groups costumed in red, black, and white. The dancing on both tiers generally operates on diagonal groupings blunting the usual front facing orientation. By the end of the piece all possible combinations of color and grouping have been exploited. Some of the movement patterns return or are recycled. The steps and overall movement are clearly ballet based but danced always with outstretched opened arms and unbending bodies. They are not complex but the density and variety achieved by repetition, regrouping, and direction shifts are. The movement is cool, almost meditative, the faces expressionless. The steps are well-grounded and only occasionally airborne, the spacing severely geometric. Like similarly charged particles, the dancers sort out some natural state of equilibrium while they move and when they come to rest.

The more you watch “Available Light” the more you appreciate the sense of risk and concentration involved.

Adams describes his music here as a representation of light on water. It was written during a sojourn on the California coast. Its textures are undergirded with drones, washes and ambient sound that at times obscure any sense of a pulse. The sound engineering for the music (Mark Grey) which combines live brass overlaying a synthesized base was beautifully presented. The red lighting (was this a literal sunset or something else entirely) for a slower section of the work seemed a misstep, a distraction from the glowing white light that made the floor feel like a shallow pool. The women looked steely and powerful, generally more so than the men.

The more you watch “Available Light” the more you appreciate the sense of risk and concentration involved. Like the relentless percussion motives driving Ravel’s “Bolero”, the transparent rhythms are easy, but for the player, staying alive in the middle of all the sameness becomes a kind of quest. “Available Light” may in fact be minimalist dance but it is risky minimalism, and in Saturday’s performance it was compelling.